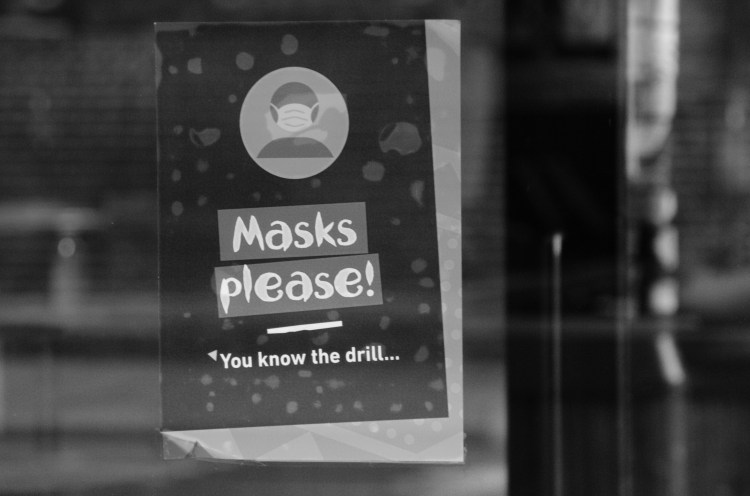

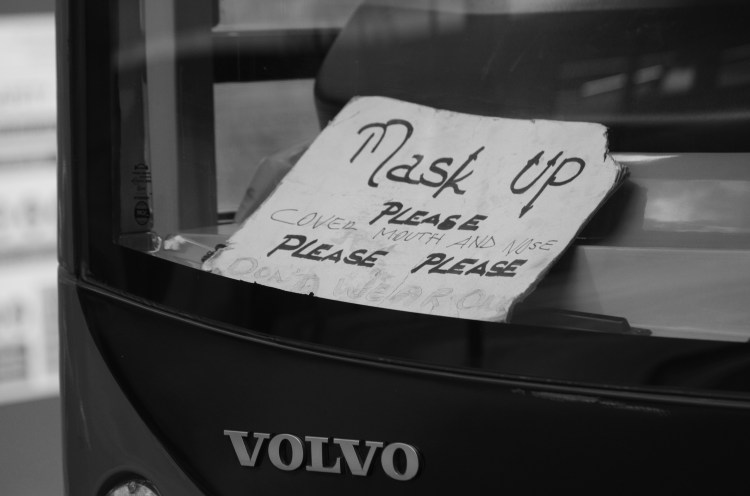

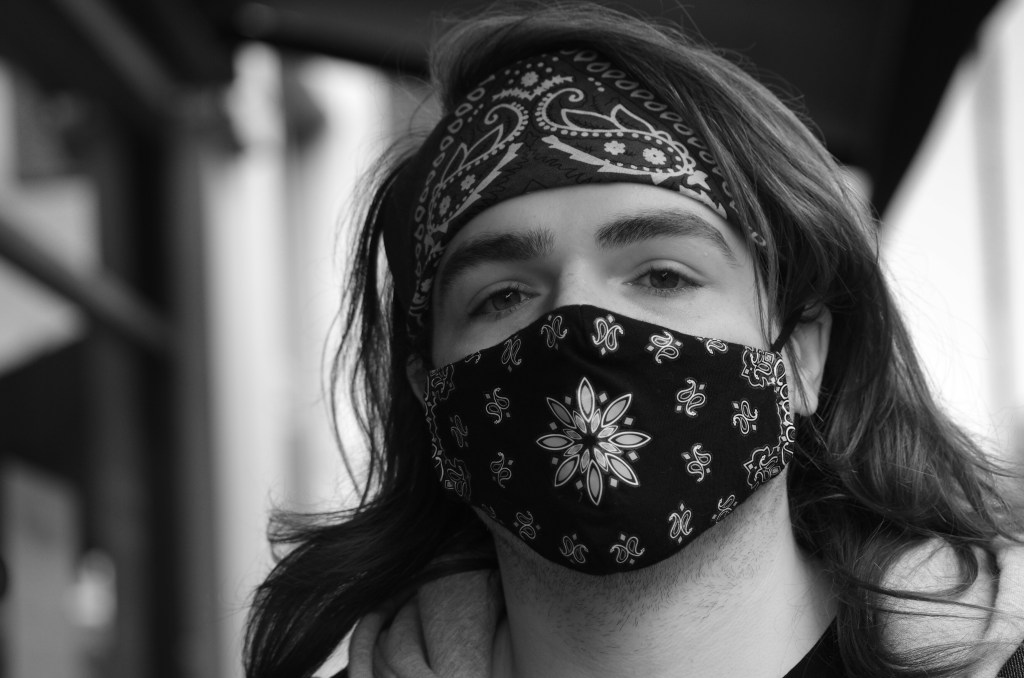

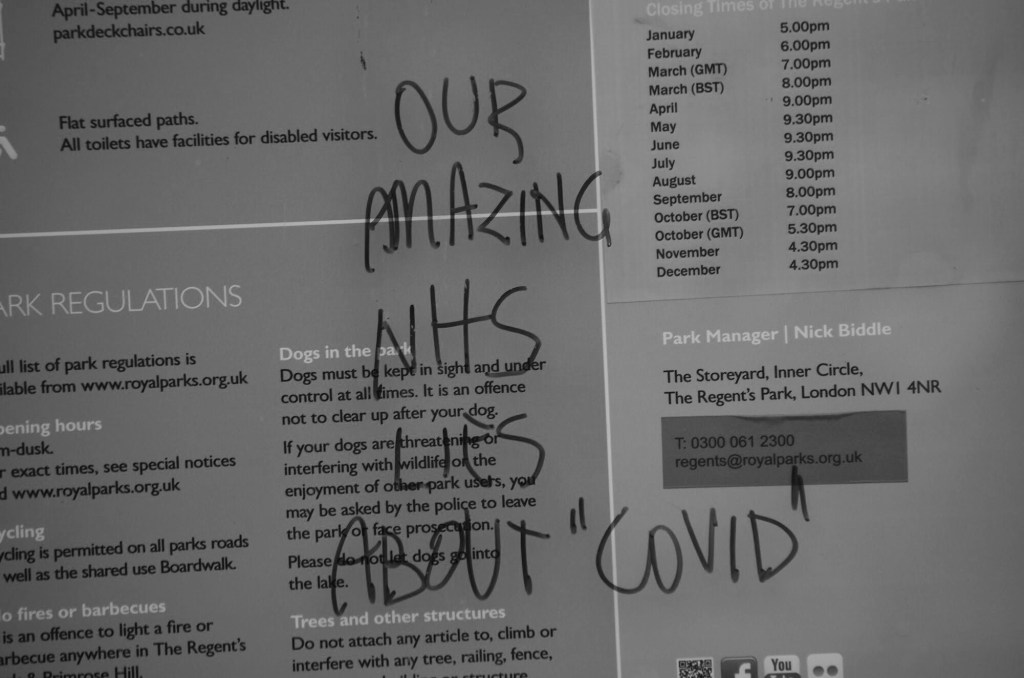

Without any hard data to back this up, I suspect that one of the few economic beneficaries of the pandemic may be the graphic design and printing sectors. In the last year, we have been confronted with a profusion of signs, placards, stickers, floor decoration and other material intended to remind us of the measures we should all know by now: wear a mask, maintain social distancing, and wash your hands. As one walks along the streets of London, there is a huge diversity of this material on doors, windows, even taxis and buses. At Kings Cross, the screen looms above the cavernously empty ticket hall.

Some of it is corporate, some of it home-made. Some of it deals in symbols reducing “face” and “mask” to their essential shapes, some use clipart cartoons which denote gender, age, and even ethnicity. All of it, however, is confronting the same challenge: to balance the need to create clear rules and prohibitions while at the same time encouraging customers. No cafe or restaurant or bookshop or supermarket wants to turn people away, but nor do they wish to spread the disease or draw the wrath of others.

Materials must be firm, emppowering staff to resolve disputes and protests with the minimum of fuss and the associated risk of exposure. And they must present the establishment or institution as responsible and aware of the risks. This is quite a challenge and the process is not yet over: social distancing and masks are likely to be with us for some time. If the idea of “vaccine passports” goes ahead, a way will need to be found to communicate the new reality again.

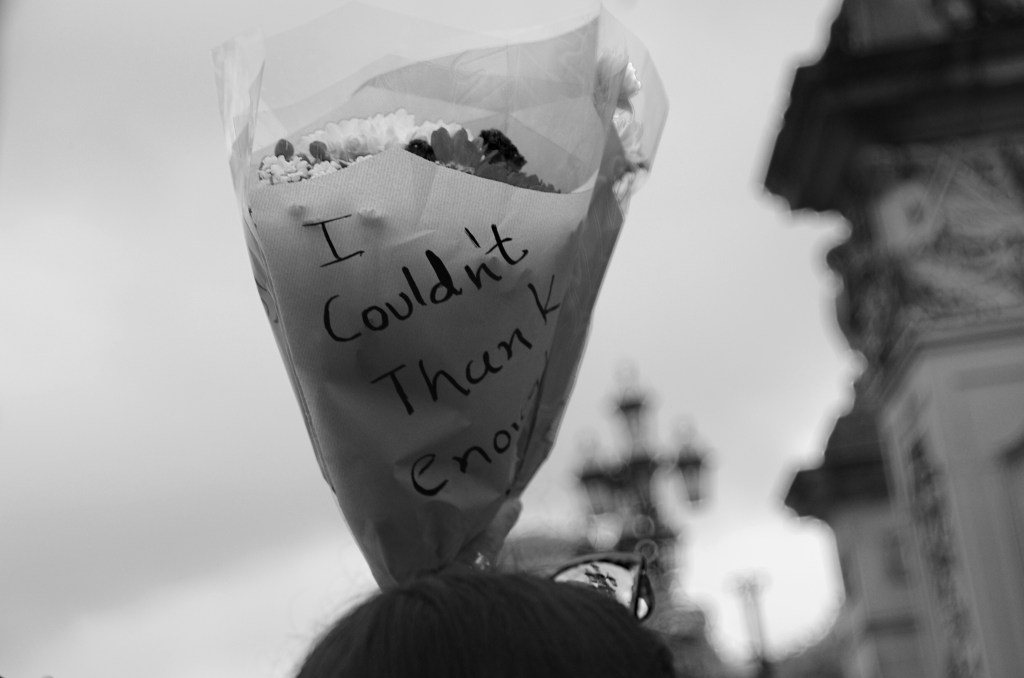

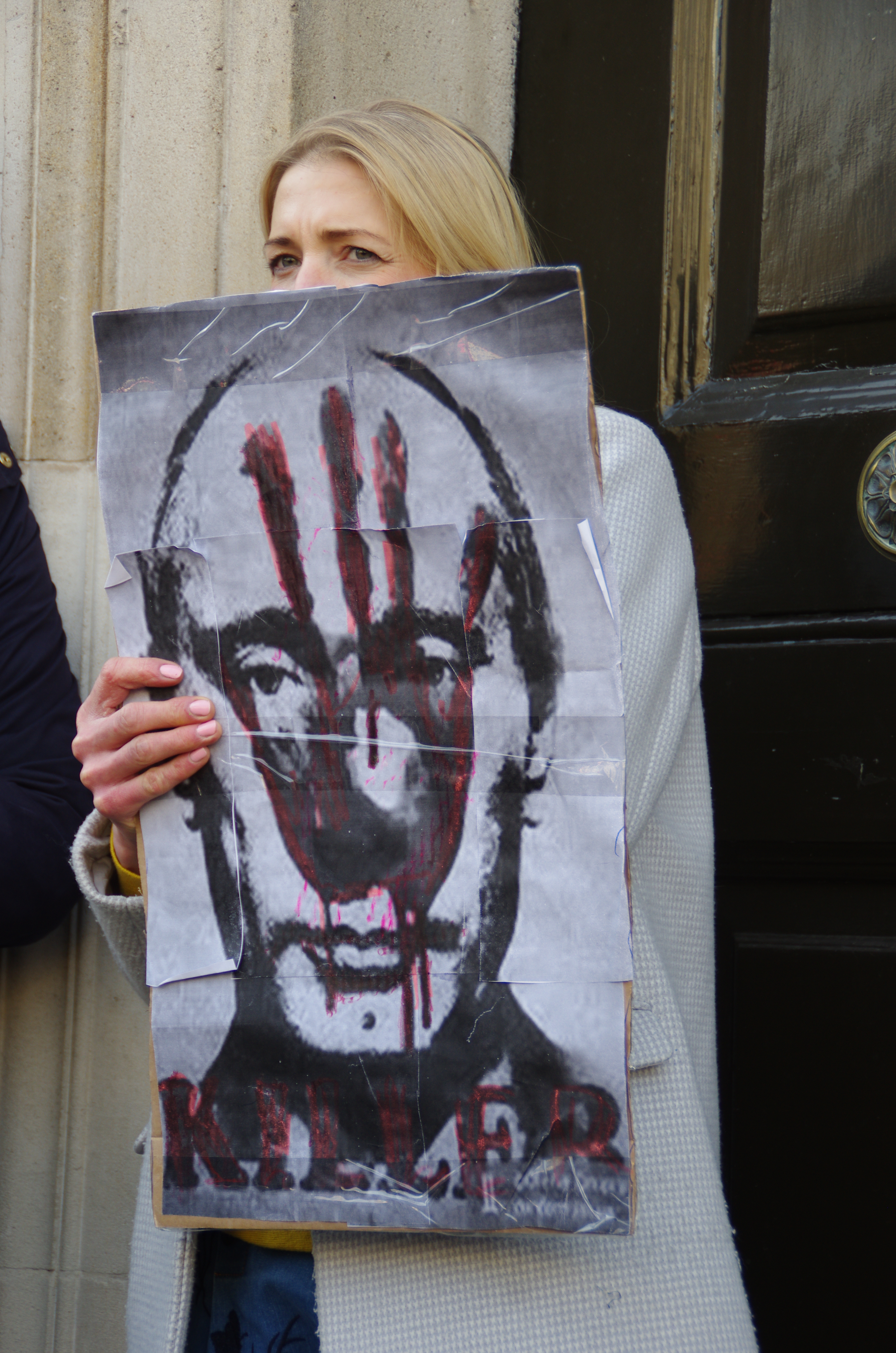

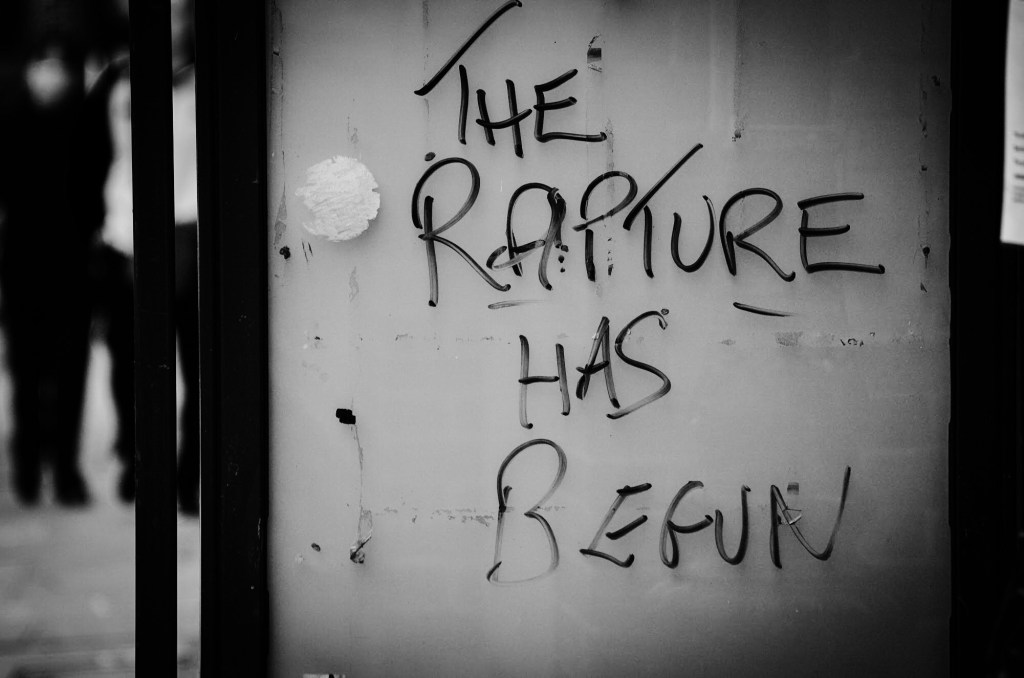

in any event, these tableaux of stickers, posters, labels and so on will constitute an essential part of any history of the pandemic. I doubt that these will become as iconic as the Ministry of Information productions of WW2 – it is in fact a real regret of mine that these were not more directly repurposed. After all, Coughs and sneezes spread diseases – help keep the nation fighting fit! The echoes of the war are to be found though:

But the history of WW2 iconography shows that cometh the hour, cometh the symbol. Keep Calm and Carry On, the suburban mantra of the 2000s and 2010s was deemed too patronising for Britain during the war; but it served as a faux-historic icon for the (misnamed) age of austerity under the Cameron-Clegg coalition, and then the jittery histrionics of the yawning gap between the 2016 referendum and our eventual departure from the EU. The flimsy nature of its symbolism is shown most clearly in that it has been less present in the last year – when it might have been vaguely appropriate – than before. As ever, history will be written in the future, understanding will come after the fact.